Balthus (Balthasar Klossowski), Thérèse Dreaming, 1938, New York, New York. {Fig. 1 }

Balthus’ Thérèse Dreaming in the Age of #metoo

In December 2017, I came across a New York Times article entitled, “We Need to Talk About Balthus.” The piece detailed the genesis of an online petition created by sisters Mia Merrill, 30, and Anna Zuccaro, 26 that sought to “remove, or at least reimagine” (Bellafante) the painting, Thérèse Dreaming, by French-Polish artist Balthasar Klossowski, better known by his childhood nickname, Balthus (1908–2001). Now several months later, I still find myself referring to the article and seeking out additional material on Balthus and his work. This research has led me to reexamine the painting in terms of three questions: What is my interpretation of the painting? Is the artwork separate from the artist? How do we determine context?

Thérèse Dreaming

Painted with oils in 1938, Thérèse Dreaming (Fig. 1) is a fairly large work measuring 59” x 51”. It is a formal composition painted in a realist style, using a mostly analogous palette of reds, orange-reds, and oranges with some complementary greens. The setting is a sparsely furnished artist’s studio. The subject, an adolescent girl, Thérèse, is posed sitting on a bench with one foot on the floor, and the other leg is bent at the knee with a foot resting on the bench. Her legs are parted exposing her underwear and slip; her skirt is rolled up to her waist. Thérèse is resting her hands on her head; her elbows are bent. Her head is turned to the viewer’s left, and her eyes closed in reverie as she rests on a green pillow. On the floor is a large, grayish cat sipping from a saucer of milk. Thérèse’s pale skin and her erotic posture hold the viewer’s attention. She and the cat seem unaware of one another.

My Interpretation

Merrill’s petition for reinterpreting and/or banning the painting is in response to her being “shocked to see a painting of a young girl in a sexually suggestive pose” (Bellafante) hanging in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. While the work may be disturbing and risqué, it is not sexually explicit. I agree with Magada-Ward that it is not pornography, which she defines as “imagery produced solely to incite sexual arousal” (23) (You only need the page # here as you used the author’s name in the signal phrase) If the painting were pornographic, there would be no scholarly debate, as it would not be considered a work of art, and we would not be discussing it with a critical eye. It is precisely the ambiguity of the subject, situation, and the suggestion of sex that lends mystery to the work and keeps viewers returning to it time and time again. Mystery is not a hallmark of pornographic imagery, but in fine art it is an asset if it raises questions and spurs conversation. Mystery creates dialogs we sorely need in the wake of myriad sex abuse scandals and the new female empowerment the #metoo movement has provided.

In terms of actual language and words, it seems one of the reasons we have difficulty categorizing Thérèse Dreaming is that we don’t have adequate language to speak about this topic with young people or adults. In my own discussions of this painting with friends in person and online, I struggled to describe my point of view and noticed others seemed uncomfortable with the terminology associated with pubescent and prepubescent female sexuality. As Americans coming out of a Puritan tradition, we find this topic distressing and difficult to discuss. If one combines those feelings with a work that teeters in a gray area between a young girl’s sexual awakening and an artist’s sexual perversion, one can clear out a cocktail party in flash.

Many viewers and critics note the voyeuristic point of view Balthus has selected for the painting, which underscores its unsettling quality. I’ve never felt this when looking at the painting, as I’m aware that it’s a painting and not reality. What I find curious about that controversy is there no male presence in the image, yet detractors seem to blame the male artist. I see a young woman alone, sexually aroused, possibly in at the midst of an autoerotic act. She is present, aware of her body and herself, and quite unashamed. From that perspective, she can be seen as empowered and in control, two overtly feminist ideas. We don’t know the subject of her dream, but just knowing it is a dream makes us uncomfortable, as dreams are the stuff of the unconscious where our most secret and honest desires dwell.

Many historians view the cats in Balthus’ painting as stand-ins for the artist. If we view the painting through that lens, we see a cat apart from the young woman. He is drinking what appears to be milk, a fluid secreted by female mammals for nourishment of their young. Perhaps Balthus is telling us his subject is a form of food for his creativity in a symbolic manner, but he keeps his distance. The gray cat is unobtrusive and in his own world, not unlike the artist.

Is the Artist Separate from the Artwork?

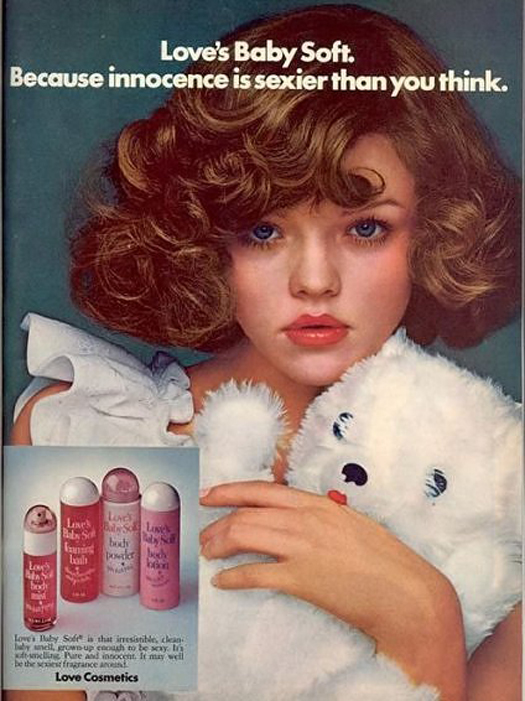

I struggle with how much accountability an artist should take for his/her work. Should Balthus have had to answer for why he was fascinated by pubescent girls? But aren’t most humans fascinated by the allure and innocence of young women? Ad men for decades have exploited this notion and created many ad campaigns based on just that very idea. In the seventies, Love’s Baby Soft sold many bottles of product using modern-day Lolitas und an unapologetic headline that proclaimed, “Because innocence is sexier than you think” (Fig. 2). I find that sentiment in an advertising context to be far more shocking than any Balthus painting. In the end, the artist and artwork are two separate entities. The artist cannot control a work once it has taken on a life of its own. As many historians note, Balthus thought the artist was secondary to the art. I again agree with Magada-Ward that “perhaps, then, the ethical value of considering his art might reside in how these paintings force us to confront the dialectical play between innocence and desire” (24), much as Tennessee Williams did with words.

Context

Merrill would like to see additional text added to the display of the work to provide context. In her words, a statement such as, “The artist of this painting, Balthus, had a noted infatuation with pubescent girls and this painting is undeniably romanticizing the sexualization of a child” (O’Neill). I would like to suggest that context is based on consensus, and clearly as a community we are not in agreement about this work. The Met has stated it will not remove the painting, and in my opinion it shouldn’t. Merrill’s statement is flawed and presents a point of view that is not necessarily based in fact. It doesn’t reflect the point of view of all viewers, including me. Balthus may have been preoccupied with pubescent girls, but there is no evidence I could find that he acted upon those thoughts, or was sexually aroused while in the presence of his young female models. Merrill’s statement is a moralized opinion that makes a judgment. In presenting the statement as it is written, she is foisting her point of view on potential viewers. Placing such a statement on a typeset plaque gives it an authority it doesn’t deserve. I would like to the opportunity to view the work for myself, without instructions. I believe Merrill’s petition is really a response to her own inability to make sense of the painting and her own discomfort about girls and sexuality. The content of a work may stay the same, but the context is plastic and will shift and change depending on the issues of the day.

One final note, I don’t know if Balthus’ models were paid or how their consent was handled. But going forward, in the age of #metoo, we can ensure models are protected and paid.

In conclusion, I believe art is the last bastion of personal freedom, and no matter how distressing, it should not be censored. Where else can someone transform inappropriate feelings and desires into visually compelling art that challenges stereotypes, spawns dialog, and offers multiple interpretations?

Love’s Baby Soft print ad, circa 1972 [Fig. 2]

Works Cited

Balthus (Balthasar Klossowski). Thérèse Dreaming. 1938, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed March 25, 2018.

“We Need to Talk about Balthus.” New York Times, 8 December 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/08/nyregion/we-need-to-talk-about-balthus.html. Accessed 17 March 2018.

“New Yorkers Call for Removal of Met Painting that ‘Sexualizes Girl.’” New York Post, 3 December 2017. https://nypost.com/2017/12/03/new-yorkers-call-for-removal-of-met-painting-that-sexualizes-girl/. Accessed March 10, 2018.

Ward, Mary Magada. “The Virtues and Dangers of Connecting Art to Life: Can Pragmatism Address Balthus?” Journal of Speculative Philosophy, Vol. 25, No. 1, 2011, pp. 22–32.

Recent Comments