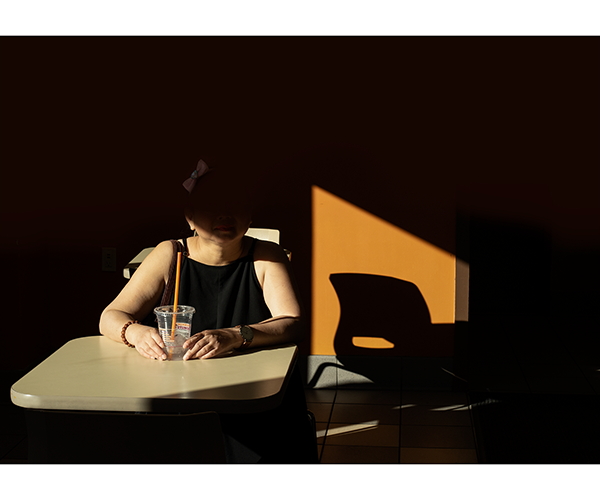

Woman with a Bow, Somerville, MA 2018

Last month the Museum of Modern Art broadcast a livestream lecture with a question and answer session called Expanded Portraiture. The event was held in conjunction with the MoMA’s current show Being: New Photography 2018. In the video, artists and curators discuss traditional and contemporary portraiture and are asked three specific questions by the moderator: what is a portrait; can a portrait be absent a person; and if anyone can make a portrait, how does that change your practice? I found those questions thought provoking and in this essay will discuss each in detail.

What Is a Portrait?

As someone who considers herself a primarily a portrait photographer, I ask myself what a portrait is every time I work with a sitter. The act of orchestrating a portrait is a collaboration with the subject, but the final image is my interpretation of the subject and the environment. The portrait in not the actual person; it is not the artist. For me it is the representation of an idea. As MoMA panelist Louise Stewart, a curator at London’s National Portrait Gallery notes the portrait “becomes a substitute for the subject” (MoMA). Taking that idea one step further, I would like to suggest that the final portrait artwork can be a substitute for the subject entirely. A compelling portrait evolves into entity unto itself, divorced from its subject, a total artwork that stands on its own. For the work to be understood we don’t need to know any specific information about the subject.

Many images by Diane Arbus illustrate this totality. Her practice of “finding the astonishing in the commonplace” (Arbus) set her work apart during the 1960s. Her selection of the commonplace and banal—her notice of it—elevated the subject and made it inclusive. As any photographer knows, the astonishing is ephemeral, and in 1/250 of a second the remarkable can vanish, with the viewer questioning if it was there at all, or if it was a contrivance of the photographer. I reference Arbus’ famous Boy with a Toy Hand Grenade In Central Park photograph (Fig. 1) and Sally Mann’s astute assessment of the analog process of reviewing contact sheets and taking multiple frames with only fractions of a second between each frame. Arbus shot eleven frames of the askew little boy and as Mann points out “Your eye would go straight for the one in which for the briefest split second the exasperated child is shown spasmodically clenching his hands, one holding the grenade, and grimacing maniacally” (Mann 290). That one frame we view in totality; we don’t need to know the boy’s name, who he is, or what he was doing in the park. He has lent his body to a elevated form of portraiture, one that is a perfect expression of an idea unto itself. Arbus’ photo is less a portrait of the boy than it is a portrait of a moment in time. Curator Stewart believes artists need to “push at the definition of portraiture” and expand the definition to “encompass places and times” (MoMA).

When a portrait is artistically successful the artist is connecting with the subject and with an idea of the subject. Amy Sherald, the painter of the official portrait of Michelle Obama (Fig. 2) commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., was drawn to Mrs. Obama. As Mrs. Obama recounts of their first meeting, “There was an instant connection, a kind of sister-girl connection.” In that meeting in the Oval Office, Sherald remembers turning away from the president and toward Mrs. Obama and saying “I’m really hoping you and I can work together.” Sherald, who is African American, has done extensive photographic research of daguerreotypes featuring African Americans sitters, as there are so few historical portrait paintings depicting African Americans. This research paired with Sherald’s desire to create formal portraits that elevate and dignify her subjects in the same manner in which white men and women have been portrayed in portraits for centuries is integral to her creative process. Sherald made a connection with Mrs. Obama, one that is inline with her idea of of the first lady. Sherald, in her words, created a “first-lady queen” in her portrait of Mrs. Obama (MoMA). I believe artists are motivated and influenced by their connections (conscious or unconscious) with the sitter, and its these associations that build more powerful works.

Can a Portrait Be Absent a Person?

When I first began photographing people, I was mesmerized by faces, so much so that I abandoned all other forms of photography, as the faces rendered landscapes and still lives unexciting and predictable. My earlier portrait work is very traditional in what Sontag describes as the “normal rhetoric of the photographic portrait” (Sontag 30) a pose “facing the camera signifies solemnity, frankness, the disclosure of the subject essence” (30). At its most universal, a portrait is the essence of the subject, but that subject is not limited to people; a portrait can be any reflection of an essence or idea. As Lisette Model observed of Arbus’ work the more specific the subject matter, the more general it became.

In my recent work I’ve experimented with an idea I call portrait obscura where the subject’s face is either completely covered or out of view. In these portraits I attempt to anonymize and generalize the essence of the idea by using the human figure but not a specific individual (Fig. 3). This is a new method for me, and I often make rough sketches of the ideas before hand, find the location, and take test shots prior to shooting.

If Anyone Can Make a Portrait, How Does That Change Your Practice?

We are currently living in time when portraiture is experiencing a rebirth due to the accessibility of smartphones and social media, similarly to when Kodak released its smaller, portable cameras in 1888. As Adatto points out, “Americans grasped from the start that portrait photography was an art: the art of rendering an image that tells us the truth about its subject” (43). Portraiture is still an art, but truth is not the primary goal; with digital artifice making it impossible for the viewer to determine what is true, it comes back to the visual idea being expressed in the portrait.

New technology has changed the way we make portraits and has changed my practice. I’m not interested in selfies as the people around me are far more captivating than myself. My process is less about happenstance and luck and more about planning and art directing. In many ways I’ve returned to the slower, older procedures when “the photographer had to carefully arrange light, lenses, and the composition of the frame” (Adatto 43). I try to work slower, think more about the idea I want to express, and create a set with actors that align with that thought. I choose an environment, colors, clothing, and form a loose narrative. I attempt to create pictures with either mystery or surprise. As my teacher, Magnum photographer Constantine Manos used to say, “A great photograph contains a surprise.”

I’m inspired by the astounding work of photographer Deanna Lawson and how she transforms struggling, working class African Americans into strong, complex, celebrity-deities that are light filled and beautiful (Fig. 4). Lawson’s exemplifies contemporary art direction and a singular point of view. As artists we are differentiated by our perspective and our powers of interpretation. In the end a portrait is a subject presented in a particular way by an artist, and that presentation is a visual manifestation of a method of practice and a specific idea.

Fig. 1. Arbus, Diane. Boy with a Toy Hand Grenade In Central Park. 1962, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 2. Sherald, Amy. Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama. 2018, painting. National Portrait

Gallery Fig. 3. Powers, Eileen. Untitled. 2018, photograph.

Fig. 4. Lawson, Deanna, Baby Sleep. 2009, photograph. Collection of the artist.

Works Cited

“Expanded Portraiture | MoMA LIVE.” YouTube, uploaded by The Museum of Modern Art, 18 April 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7dqgNKvieAs&t=2s.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1973.

“Masters of Photography: Diane Arbus or Going Where I’ve Never Been: The Photography of Diane Arbus” YouTube, uploaded by Dimitar, 10 January 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q_0sQI90kYI&t=1539s.

“Painting Michelle Obama,” Sidedoor podcast. Smithsonian Institution, 18 April 2018, https://www.si.edu/sidedoor/ep-23-painting-michelle-obama.

Adatto, Kiku. Life in the Age of the Photo Op. Princeton University Press, 2008.

Recent Comments