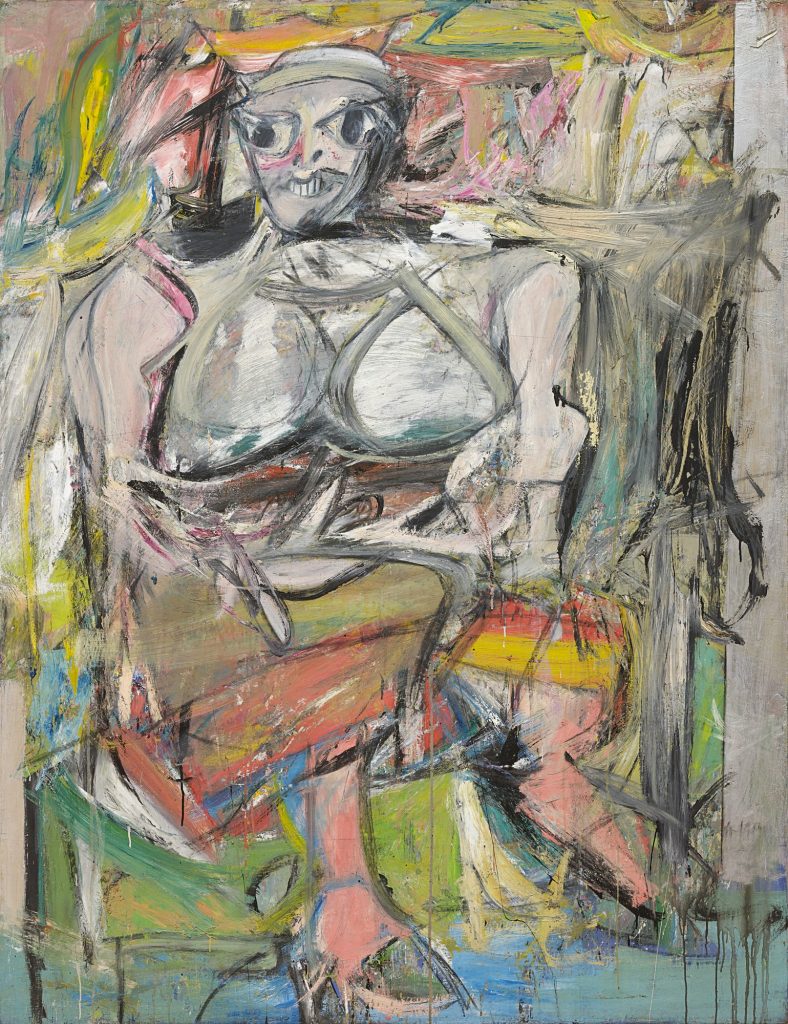

Willem DeKooning’s Woman I {Fig. 1}

Comparative Analysis:

Willem de Kooning’s Woman I and Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Pygmalion and Galatea

At first glance, Willem de Kooning’s imposing, frenetic masterpiece, Woman I, appears to have little in common in with Jean-Léon Gérôme’s precise and controlled Pygmalion and Galatea. The de Kooning is large and brash; the Gérôme is compact and subtle. If placed side by side in a gallery setting, the two works would offer a study in contrasting painting styles and content, but for all their dissimilar qualities, there are many similarities: the idea of transformation, the artist as Pygmalion, and the depiction of an imagined sexuality.

1. Woman I

Completed in 1952, de Kooning’s abstract expressionist Woman I (Fig. 1) is a massive oil painting measuring 6’3 7/8” x 58”. The painting is of a large, seated woman who fills most of the canvas. She is wearing what appears to be a white sleeveless blouse and an orange and yellow striped skirt. The blouse is painted with energetic brushwork that accentuates the woman’s ample breasts and extra-wide shoulders; her claw-like right hand rests in her lap. The woman’s legs are parted slightly and she is wearing green shoes. The figure’s head is large, with a pair of oversized black and gray eyes, shocks of black hair resting on her shoulders, and, most notably, a mouth that resembles a toothy sneer. She is a monstrous female—supersized and threatening. The figure and accompanying background is painted in an aggressive, explosive, free-form style. The brushwork is informal, even infantile, and the surface texture is rough and uneven. The location is unspecific; it could possibly be an artist’s studio. At the left side of the painting is a wall or partition.

In terms of color, the top portion of the figure, including head, arms, and breasts, is painted in whites, grays, blacks, and some pinks. Her legs at the bottom of the painting are flesh-toned and vibrant. From afar, the entire painting is multi-hued with greens, yellows, oranges, blues, pinks, and reds. The composition is spontaneous, but well-balanced with prominent negative spaces on the right and upper right of the canvas. The mood is expressive and frenzied. The painting is in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Pygmalion and Galatea. ca. 1890, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [Fig. 2]

2. Pygmalion and Galatea

Gérôme’s representational work Pygmalion and Galatea (Fig. 2), ca. 1890, is an academic-style depiction of the classic myth of the same name, one of the many stories found in the narrative poem Metamorphoses by Ovid. Painted in a formal, Orientalist style, Gérôme’s command of the paintbrush creates brushwork that is nearly invisible. The paint is applied in a smooth and exacting layered manner, with the figures placed just left of the center of the canvas. The setting is an artist’s studio and shows the artist, Pygmalion—the king of Cyprus—sculpting a female nude figure out of white marble or ivory. The artist has put down his tools and is wrapped in an embrace with the figure, Galatea. As they kiss, the half-human, half-sculpture Galatea, is gradually coming to life, thanks to the pierce of Cupid’s arrow. Cupid floats in the mid-upper right portion of the painting, with his bow drawn and poised to take another shot. In the background, we see the artist’s scaffolding and various maquettes on the shelf. On the back wall of the studio is a painting, presumably by the artist: a shield with a face and two heads on the far right, one painted in flesh tones, the other pale and ashen.

The color palette is analogous and the composition is planned and formal. The most striking aspect is that the sculpture is coming to life: Galatea’s flesh transforms from cold ivory to a life-like peach-pink. The background is painted in dark greens, complementary to the pink/peach colors of Galatea, bringing her forward on the picture plane. Gérôme’s work is hallmarked by its insistence on accuracy and veracity (Nochlin 47). The entire scene is masterfully contrived and romantic. The mood is both serious and joyful. The painting housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

2. Transformation

I chose these two paintings because I saw them when I was very young and still in grammar school. My Aunt took me to both to the MoMA and the Met where we viewed Woman I and Pygmalion and Galatea, the second of which I had as a print hanging in my room. I was fascinated by Galatea’s transformation from bottom to top, from statue to animate being, ideal woman and mate. In my print and in the painting, it’s fairly obvious that a transformation is occurring. Her flesh is coming alive—from her stony feet to her vivid head. The diagonal angle of her body lends a sense of motion and animation; she feels real and of this earth. We see Gérôme’s skill and technique displayed, especially in Galatea’s upper thighs and buttocks as her skin goes from pale to lifelike. The viewer believes this transformation without question and expects a happy outcome for the couple.

In contrast, the transformation in Woman I is veiled, and the change is in the opposite direction, both literally and figuratively. de Kooning’s Galatea transforms from top to bottom. The top half of the figure is painted stony and white in color; she is sculptural in a way, with touches of pink and life. The manner in which her white blouse is draped over her breasts is reminiscent of classical Greek sculpture, with its elaborate fabric representation sculpted in folds and fitted over the female form. In contrast to Pygmalion and Galatea, the feet and calves of Woman I are fleshy and alive; her orangey skin is accentuated by her complementary green shoes. This treatment suggests that Woman I was alive and vibrant but is slowly being transformed into a “Gorgon,” (Duncan 173) a monstrous, dreadful, pale, guttural beast with teeth reminiscent of fangs. We expect Woman I to growl and turn us to stone. We viewers are in danger of being transformed, whereas Gérôme only wants viewers to revel in the cheery side of the myth and be titillated by his socially acceptable form of pornography. His, after all, is a salable painting, and Gérôme chooses a subject and a style that work to “increase its value as a product on the art market.” (Nochlin 49)

3. The Artist as Pygmalion

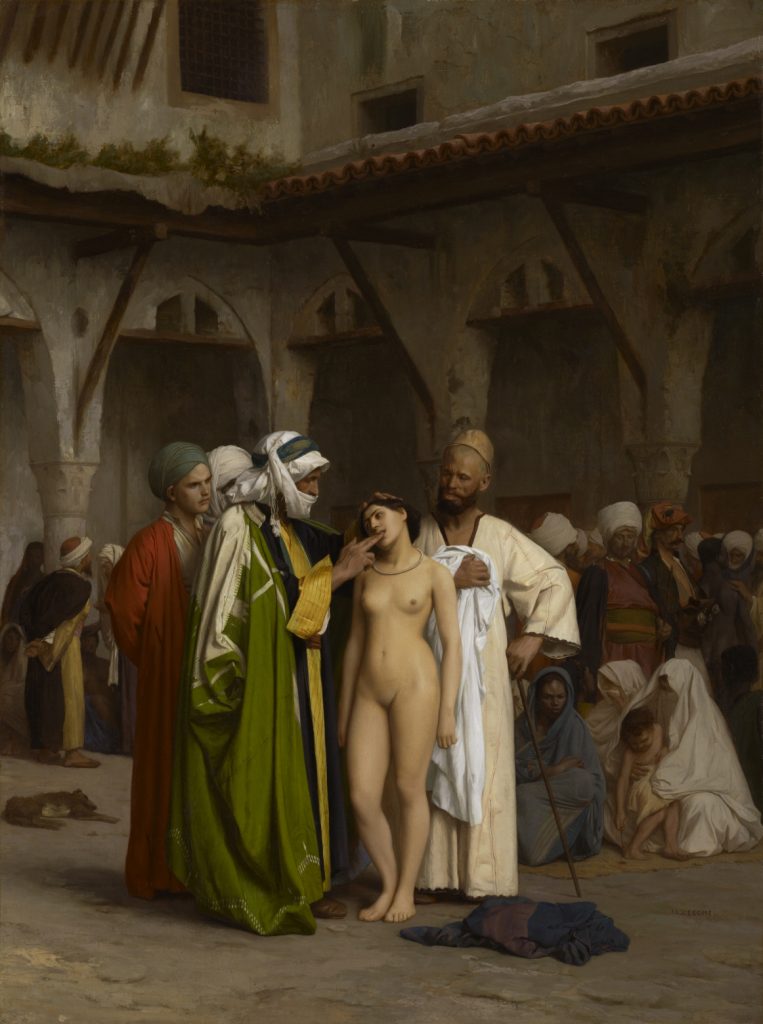

One aspect of Orientalism is its portrayal of foreigners as “culturally inferior” (Nochlin 34) outsiders and its assertion of “European dominance” (Nochlin 34) over eastern cultures. This dominance extends to the Orientalist’s view of women, who, I would argue, are treated as foreigners in Gérôme’s work, as outsiders requiring domination. The painting The Slave Market (Fig 3) is an overt display of man’s power over women. Synchronous to that idea is that of the mythical Pygmalion asserting his dominance over the woman of his own creation. The unmarried Pygmalion, disillusioned with women, takes it upon himself to create an imaginary ideal woman, Galatea. She is a symbol of love and fertility, but also of a woman under the control of a man.

I suggest there are two Pygmalions, Gérôme’s controlling version, and de Kooning’s out-of-control version. In Pygmalion and Galatea, Gérôme has chosen to paint Pygmalion quite possibly in his own image (Nochlin 49); the artist is part of the fantasy, and the painting is an illustration of his dream. The artist is an insider participating in the myth. On the other hand, De Kooning is Pygmalion; he is changing the Woman I before our eyes, but that change is out of control. She is becoming a nightmare, a woman-monster, threatening and horrific. We don’t know if de Kooning set out to create an ideal woman or not, but what we do know is that the combatant woman he creates is the opposite of Gérôme’s submissive Galatea. She, too, is a mythical woman and symbol of fertility, but de Kooning has taken his fear and brought it the forefront, whereas Gérôme buries it in a gorgeous representation that is totally devoid of truth. De Kooning’s woman is far more truthful and authentic, even with his haphazard brushwork and extreme color palette. Gérôme keeps the viewer at a distance so as not to affect the action in the painting; de Kooning decreases the distance between the figure and himself (and us), and by painting on such a large scale he introduces fear in his work. We feel consumed by this woman. As Carol Duncan asserts, “Very often images of women in modern art speak of male fears.” (Duncan 172.)

The viewer is an interloper in Gérôme’s paintings, which almost never include a “touristic presence.” (Nochlin, 37) In the work the artist has “inexorably eradicated all traces of the picture plane denying us any clue to the art work as a literal flat surface” (Nochlin 37) bolstering a false sense of reality, and giving the canvas a smooth surface not unlike our own sense of sight. Gérôme wants us to feel that paintings are part art, part postcard, part journalism, and an “attempt to document realism.” (Nochlin 33) We are in the room with Pygmalion and Galatea, but we’re behind a velvet rope. There is no interaction, and no reality. Whereas the opposite can be said of Woman I, which can be looked upon as a post-modernist confrontation with a woman who conjures up feelings of powerlessness (Duncan 174) in the viewer. Woman I is a direct, forceful female. De Kooning’s use of clashing colors and frantic lines underscore the fear he has for his chosen subject.

3. Imagined Sexuality

Both paintings are imaginary depictions of sexualized women. Whether or not Woman I is based on a real, breathing woman is not known, although de Kooning made many sketches and studies (MoMA) for the work. What is apparent is the imagined sexuality in both paintings. De Kooning has created a sexual tension in Woman I. Is she goddess, or is she Gorgon? Is she mother or monster? What we see is a woman front and center, with her legs slightly parted; this posture both “suggests and avoids the explicit act of sexual display.” (Duncan 173) By rendering her in this dichotomous manner the viewer is unsure of her exact sexual role. Does she want to have her way with us, consume us, or both? de Kooning poses more questions than he answers with the work, and requires the viewer to participate in forming the answers.

The purpose of Gérôme’s imaginary Galatea is never in question; the sexuality is implied in a culturally acceptable way. But unlike Woman I, we don’t have Galatea’s point of view. Her sexuality and fertility are hidden as she is painted from the back. Her sexuality is covert and shameful with misogynistic undertones. We don’t know how she feels about her union with Pygmalion; we have no sense of her. She is anonymous. This is not a concern for Gérôme; he is not interested in giving us more information about his Galatea. He lets us use our imaginations to fill in the gaps and come up with an identity for her. It’s the viewer’s role to customize the fantasy through the lens of his or her own sexual wants and desires (similarly to Woman I.) The difference is that de Kooning gives us an outpouring of raw emotion and abject fear; Gérôme gives us a classical painting with a placid surface that hides a swift undercurrent beneath it.

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Slave Market. 1866, The Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts [Fig. 3]

Works Cited

Nochlin, Linda. The Politics of Vision: Essays on Nineteenth-Century Art and Society. New York: Harper and Row, 1989. Print.

Duncan, Carol. “The MoMA’s Hot Mamas” Art Journal (Summer 1989): Pages 171–178. Print.

Woman I, Willem de Kooning, Museum of Modern Art, http://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/willem-de-kooning-woman-i-1950-52-2 (accessed February 17, 2018)

Recent Comments